by Julien Zerbone in CR(I)SES AD(JUST)MENTS (COLLAPSED), published by Lulu Press, NYC, 2013.

Over the course of several years, Christine Laquet has frequently questioned the imagery of animals, of savagery, and of the other through philosophical and poetic approaches, resulting in works where tenderness and violence mingle closely. Thus, her exhibition in the FRAC Pays de la Loire, Une brève histoire de tout (A Brief History of Everything), was built around the idea of the trap, of stalking, and of catching. These motifs reoccur throughout her recent work, whether they are observation devices (weather vane, camera obscura), materials and devices related to restraint and confinement (bird cages, nets, barbed wire …), or dead animals, mounted or not. However, this idea of the trap is not merely an image, a theme or an illustration. It is rather the artist’s own methodology and its display, a way to address the audience and to create the conditions to another way of seeing the world and beyond. We, in turn, desire to question these traps set by the artist through several pieces from her last exhibition in order to understand its motivations and its mode of operation.

Vanity – Photography on Diasec, 2012.

Vanity – Photography on Diasec, 2012.

Act I

Taken in its metaphorical sense, the trap can be seen to illustrate our modern scientific attitude towards the world and the procedures that we put in place in order to know and claim it. We trap particles in particle accelerators, we capture specimens for study, we build museums in order to store human remains and objects from an entire culture. Our scientific and cultural institutions are a huge trap that recreates « in captivity » natural phenomena and mounts cultural facts, bringing them to a discourse where they are both included and understood.

More specifically, the pattern of the trap illustrates a principle of asymmetry defined by the philosopher Bruno Latour as being a principle specific to Western modernity. On one side there is belief, nature, irrationality; on the other, culture, reason, science. On one side the Western man, on the other flora, fauna and the human and mineral worlds, all together taken in by his own knowledge and discourse. The world is pitted against the Western man, who is locked up in his own trap… It is on these distinctions that Christine Laquet sets her field of investigation and creates stories or rituals, at times in reference to previous or alternative constructions to modernity (shamanism, animism …), at times questioning the histories of its development (the story of the wild child in Nous nous sommes fortement influencés, Darwin and Einstein in Recife, etc..), and at times reinventing fairytales in order to build other ways of seeing the world: Peau d’Âne, Les Fables de La Fontaine, etc… If there is a trap in the artwork of Christine Laquet, it is primarily from a poetic, narrative and methodological point of view.

Une brève histoire de tout is the eponymous artwork of Christine Laquet’s exhibition. It is also an introduction: the work itself is a double metal door that we are invited to push open to see further. Its structure consists of letters spelling these instructions. These are repeated, overlapped, and meant to be read in a variety of directions. The letters are progressively deformed until shaping a strange and poetic glossolalia. The artist offers to us to pass through language in order to engage with the exhibition, to see ourselves. However, for many anthropologists, this very language marks the fundamental difference between humans and animals. It embodies our rationality, our ability to abstract the world and put it into signs. Abandoning language and giving into glossolalia has us is to erase any distance, and to accept being lured and taken in. A literal and figurative trap, the door establishes a false alternative: either we stay on the threshold and we look through the grid or we accept to get trapped and close the door behind us. Thus we are trapped ourselves, we are captivated.

A brief history of everything – 2 steel reinforcement bar gates, 40,9 x 70,9 inches (x2), 2012. (Photographie © Marc Domage)

At the roots of this exhibition, there is an archive from a close relative of the artist, who has set up camera traps at the heart of a French mountain range. Driven by his passion for wolves, the amateur scientist set up the photographic devices and hid them in the stumps near sites in the Vercors where animals come to drink. He sought to capture their presence, to count them and get to know them. The results are snapshots of animals made from an automated mechanism triggered by their passage nearby. “These animals – says the artist – are trapped in the image. The poses refer to the act of photography itself. Its violence, poetry, beauty. The animals are captured in a shot, both actors and prisoners, bearing witness. This technique brings it close to surveillance cameras in natural spaces. ” These “shots” are commonly used in order to establish a set of statistics on the main caracteristics of the wildlife in the area, their habits, their reproduction. Shown in this exhibition, these images are no longer tools; they become objects of contemplation and wonderment, loopholed and incomplete but embodying a new poetry.

Act II

Christine Laquet made a video out of these archives, and called it Tir de nuit (Night Shot). The title refers to a triple reality: predation on one hand, doubt and silence on the other, and lastly, ghostly appearances from the night. On the screen, it is neither a movie, nor still images: at night, slopes of dirt, ponds, bushes and trees all stand out; white against the dark background. The shadow of an animal appears in several pictures; it disappears and appears again a meter away, sometimes joined by another fellow creature. The absence of color, the small number of shots per minute and the infrared lighting give a ghostly appearance to the deer, wild boars and the wolf that all bathe, play, fight, and drink in complete silence. The image is deeply deceptive and at the same time greatly fascinating. In a clever manner, the artist creates suspense by delaying the hero’s appearance until the end of the film: the most expected character, but whose presence would prevent the others from showing themselves: the wolf. Perhaps is it to emphasize the deductive aspect of such an un understanding, in which being absent can mean as much as – or more than – being present, where what we see is only the expression of a negative network/patchwork, an intimate knowledge of a territory, its species and their habits …

Night shots – Photography animation, video. Length: 5min40, 2012.

This network, precisely, is lacking. The lack of information in the “raw” aspect of this archive creates both the ambiguity and the singular interest of the artist’s approach. In Night shot , it is indeed important to question what we cannot see it. There is no indication of place nor time, no contextualization of these “scenes of daily life”, the field of vision is limited to only a few meters. All these elements contribute to the feeling of an old silent movie … In its materiality, both in its obvious and its deceptive appearance, in its intimate strangeness – Night shot introduces us to the “point of concern” evoked by Georges Didi-Huberman in Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde and experienced by the viewer who feels caught between the tautological vision embodied by the famous “what you see is what you see” by Frank Stella, and the hoping vision according to which there is always something to see beyond. “To see is to feel that something inevitably escapes you”, explains the art historian. It is to experience loss, and this is undoubtedly what we feel with these fugitive apparitions. They challenge and question us in their silence, without giving us the keys to any type of discourse. It is therefore a two-way visual trap that captures its prey whilst throwing us, the viewers, into a world of confusion and awareness of our lack of position. Us, those who watch without being invited to do so. And those who witness the spectacle of our own absence, that of Nature, as she is, as she denies us. A somewhat ironic vision of a viewer who feels watched more than anything…

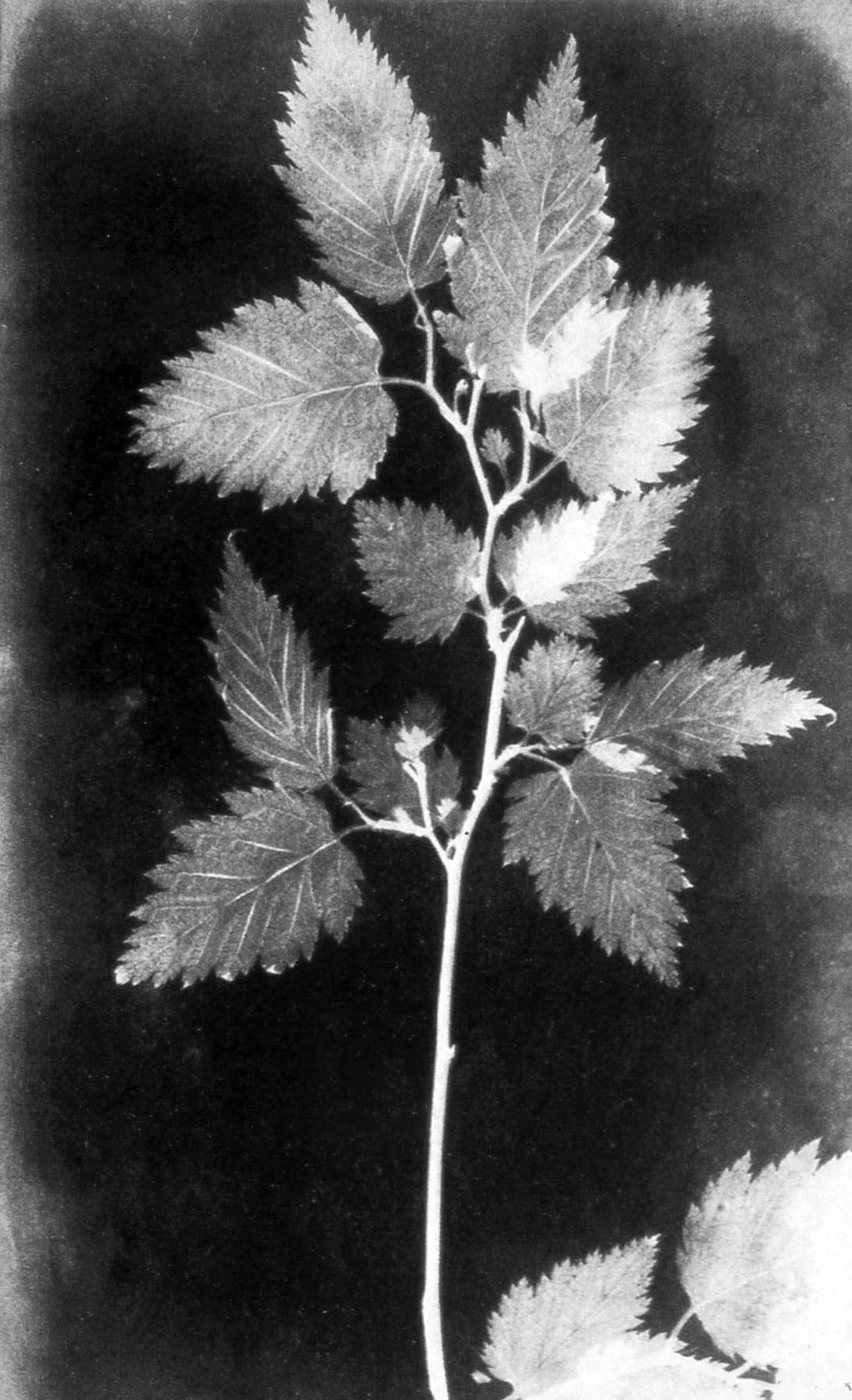

William Henry Fox Talbot – Botanical specimen

These figures emerging from the night are embodied in three enigmatic paintings by Christine Laquet. Larger than life and painted in black and white on transparent veils, a deer, a wolf and a stag, stare at us with their bright eyes. Their gazes challenge us – as was the case in Night shot – through the powerful white of their eyes whereas the rest of their bodies are barely sketched in an evanescent transparency. This gaze is not aimed at us, but keeps us at a safe distance. In their fugitive way and their shadowing materiality, these figures remind us of the “photogenic drawings” that Talbot, a pioneer of photography, devised in 1839. He described it as « a process by which Natural Objects may be made to delineate themselves without the aid of the Artist’s pencil ». Closer to the photogram than to photography, this device consisted in putting into direct contact the sensitized paper and the object. The idea was that “It is not the artist who makes the picture, but the image which makes itself “. Photography is for this reason the natural art par excellence, the receptacle of an autopoietic nature printed, as it is, thanks to the light, without any human intervention. As light footprints, these paintings escape the categories and our gaze and remind us of our constant need – along with our fear – of a naive, direct and total relationship with the world, in order to see all borders and all limitations in our perception of what surrounds us vanish.

Ways of Seing (the wolf) / (the hind) / (the deer) – 3 acrylic and japonese ink on polyester net, 118,1 x 78,7 inches (x3), 2012.

Trapeze – Suspended sculpture fully realized in glass (cords, bars and hooks), 55 x 26 x 3,9 inches, 2008.

(Photography © Marc Domage)

Therefore, the whole system set up by the artist, the seemingly scientific nature of the shoot, the apparent simplicity of her paintings are themselves traps: we are caught between different regimes of seeing and knowing, between a form of intimacy with wild emerging shapes on the screen and veils, and the doubt which they instill in us, between the immanence of these apparitions and their necessary background. As the man who wishes to set traps, we are reduced to a set of conjectures about what might have happened, what we imagine taking place out of our sight. Caught in his own trap, this is the situation of the viewer, watched by what he was watching, which is no longer trapped in his net … To better highlight this double trap, the artist maliciously exhibited two pictures of the camera traps, almost invisible in the lush undergrowth … We, who guessed Nature through technical devices, now face a Nature which is too obvious and seek to uncover its hidden mechanisms. This is our knowledge of the world which, with its systematic and rational appearance, is fed by more intricate stories, beliefs and poetry and is what Christine Laquet used as her favorite materials.

Photographic trap – Photography, diasec, 2012.

Photographic trap – Photography, diasec, 2012.

Act III

And get lost in the end….With You should never forget the jungle, Christine Laquet pursues a collaboration she started in 2011 with Robert Steijn, performer and dancer, on Gunung. Gunung takes its name from a Korean shamanic ritual which accompanies the souls of the dead through sacrifices. During a residence in Korea, the artist had indeed met a shaman, Sul-Wha Kim, who invited her to attend one of his rituals. The shaman had recognized Christine Laquet, she explains, even though they did not know each other. Strangeness and complexity of this meeting which abolish borders. During the resulting performance, Robert Steijn embodied a « screen-man ». He was holding the screen of this ritual, providing a physical distance and questioning our Western view on shamanistic rituals. The Performance materializes the meeting for Christine Laquet and according to her, it can not take place without a ritual. The use of body and gaze moves her practice from visual art to performance and enlarges her field of investigation. The meeting as a playground, is found in You should never forget the jungle, in the happy encountering – then erotic and ultimately tragic – between a young deer and a hunter, played by the bodies of two artists, around a boundary embodied by a knife.

You should never forget the jungle – Video of a performance with Robert Steijn, 16/9 HD, 19 min, 2012.

Just like the exhibition, it all begins with words, and in this case with hypnosis: from 10 to 1, the countdown enables a change of realities, a transformation inside the narration. The deer shows its exuberant characteristic and, while addressing the audience, explains that he must confront the hunter and give him his life. Therefore, they live a relationship which is no longer a unilateral stalking but a seduction game, a mutual and unconditional offering. The hunter is faced with an animal that looks human. Finally, the hunter, who is caught in a cornelian dilemma, shoots the deer, feeling exasperated by its dances. But this is not quite a death since it initiates a molt where limits are exceeded, prior to any ritual initiation. In cannibalistic tribes in Brazil, the conquering warriors change names when they ingest an opponent at the end of a long ritual process. Thus, after this lethal action, we see the man slip into the skin of the beast and be born again.

In his book Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga develops an argument which states that the game is the essence of man. It gives shape to culture, rituals and social structures. Christine Laquet’s role-playing game could be the essence of our relationship with the animal world. Any passage from human to animal is possible thanks to a deep mutual desire to play and be played, to give oneself to the other in order to improve. Therefore, to get out of the trap is first to accept this trap as a border, a porous playground where identities, bodies, roles are being shared, exchanged and modified. It is to build a fluid and evolving otherness by first considering the other in oneself in order to consider the self in the other better. It is about meeting the other, nature and animality and then agree to write and tell a story about this meeting, to finally transform each other.

From trap to game, from doubt to invention, from separation to crossing the boundaries. The artworks on display in A brief history of everything finally form a puzzle, a treasure hunt for the viewer who is willing to play the guessing game. Caught between fascination and doubt, taken aback by what seemed to be unveiled immediately, by a world we think we know, a world of deja-vu, we are invited to invent new rules, we move to cross the boundary, this separation which is after all the real trap.

The point is not to establish foreign beliefs and habits into European tradition here, but to understand how our relationship to the whole world is caught up in these issues, in seduction intertwined with infinite violence, in the necessity to embody another self in order to feel better that there is no radical separation from the world and oneself. So nature, animal, and human appear as artifacts developing constantly, as representations of the other that we try to personify in our turn.